G. Sealy Massingill, MD, knows well the wildly unpredictable nature of birth. The consultant on TMA’s Committee on Reproductive, Women’s, and Perinatal Health has attended the deliveries of thousands of infants and wouldn’t dare to presume that any apparently healthy patient labors unencumbered by risk.

“It is extraordinarily difficult, in fact impossible, to tease out every person who’s going to have an urgent or emergent problem during labor and delivery that requires urgent or emergent intervention,” the Fort Worth obstetrician-gynecologist said.

He’s seen “perfectly healthy young people” with apparently uncomplicated pregnancies and no risk factors spiral from “normal, normal, normal” to “disaster” in the blink of an eye. While acting as a medical director for a group of eight certified nurse midwives, Dr. Massingill coordinated with nurse-midwife and physician colleagues to oversee 50 to 100 deliveries per month. Instead of breaking into binary factions, as it might have done, the team achieved a symbiosis of sorts to best support pregnant patients and their families.

As physicians and certified nurse midwives at his facility worked together seamlessly, they manifested a sort of collegial nirvana that other teams might wish to try to replicate.

“It was a marvelous, magical time,” Dr. Massingill said, adding “certified nurse midwives are a critical piece of the health care team.”

That collaboration also has potential within the birthing center model, which, under certain safety standards, presents an opportunity to help overcome some of the state’s maternity deserts, says Rakhi Dimino, MD. The immediate past chair of TMA’s Committee on Reproductive, Women’s, and Perinatal Health is also director of Midwifery Services at Houston Methodist Willowbrook.

While the births she and Dr. Massingill typically oversee take place in a midwifery unit in a hospital, midwives also attend births in freestanding birthing centers.

These centers handle about 1.2% (4,413 births out of 380,266) of the state’s births annually, according to the Department of State Health Services (DSHS).

But the statistical sliver they represent can provide a space for “women who feel like they have not been heard,” Dr. Dimino said. “That can be due to social barriers, it can be due to discrimination, it can be due to just lack of bonding with their team. A birthing center can provide a place where they feel [comfortable] and they feel heard.”

Especially in a state that struggles with poor maternal access, “that’s a really important part [of] maternity care.”

But not all birthing centers are held to the same standards. In addition to exploring financial and other impediments to birthing centers reaching the gold standard of quality, Dr. Dimino asks: “How can we pull [birthing centers] all under an umbrella that holds them to high quality, just like we do hospitals, but not be a barrier to them in providing care?”

Addressing disparities

In 2023, Texas’ rate of preterm births was 11.1%, higher than the national average of 10.2%, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (tma.tips/BirthData). The preterm birth rate among babies born to Black mothers was 1.4 times higher than the rate among all other babies, and the infant mortality rate among babies born to Black mothers was 1.7 times higher than the state rate, according to the same data set.

TMA wants to ensure transparency and safety for those patients who choose nonhospital alternatives like birthing centers so patients can understand the differences in their care options and make informed decisions.

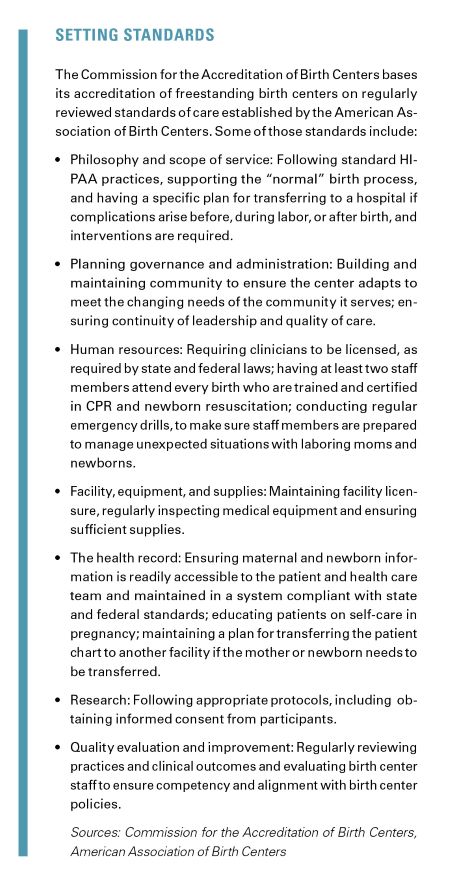

For instance, Texas allows for the practice of two types of midwives of varying credentials and regulatory oversight. And birthing centers in Texas must be licensed by the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC), but they do not have to be accredited by the Commission for the Accreditation of Birth Centers (CABC), which holds higher standards of care established by the American Association of Birth Centers (AABC).

TMA policy, recently updated at TexMed 2024 last May, supports state legislation that helps ensure safe deliveries and healthy babies by acknowledging that the safest setting for labor, delivery, and the immediate postpartum period is in a hospital, a birthing center within a hospital complex, or a freestanding birthing center that meets accepted standards, including those of AABC. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also names hospitals and licensed, accredited birth centers as the safest settings for birth (tma.tips/SafeSettings).

TMA policy also states the practice of certified nurse midwives and certified professional midwives “should only take place in consultation with regular record review by a licensed physician practicing obstetrics,” and recognizes that “each woman has the right to make a medically informed decision about delivery.”

As of this writing, Texas has 92 licensed birthing centers, only four of which are accredited, according to the most recent 2024 HHSC data available.

The CABC gauges birthing centers’ eligibility across seven standards of care developed by AABC, which include having a specific plan for transfer of a patient to a hospital if complications arise before or during labor or after birth that require interventions.

Being accredited “opens up doors for us [physicians] to provide education and provides opportunities for connection,” Dr. Dimino said.

Carla Morrow, a certified nurse midwife and founder of one of Texas’ four accredited birthing centers, also highlights a more sustainable caseload and more time with patients as benefits. But the flipside of that luxury is “none of the accredited birthing centers are able to take Medicaid because it pays such a dismal rate,” Ms. Morrow said.

Still, she agrees professional interconnection and rapport to support the health and safety of birthing parents and infants remains the overarching objective.

“We can’t do what we do and do it well and do it safely without a collaborative relationship with physicians,” Ms. Morrow said. “Our philosophy is the two disciplines work well together when there’s a collaborative model. … We all have the same goal.”

That shared goal resonates with Dr. Massingill.

And while he believes birthing centers aren’t as safe as hospitals, the more they comport with regulatory best practices and achieve accreditation, the better, he says.

“Collaborative practice is a beautiful thing when it’s done right.”